Sápmi Forever,

2022

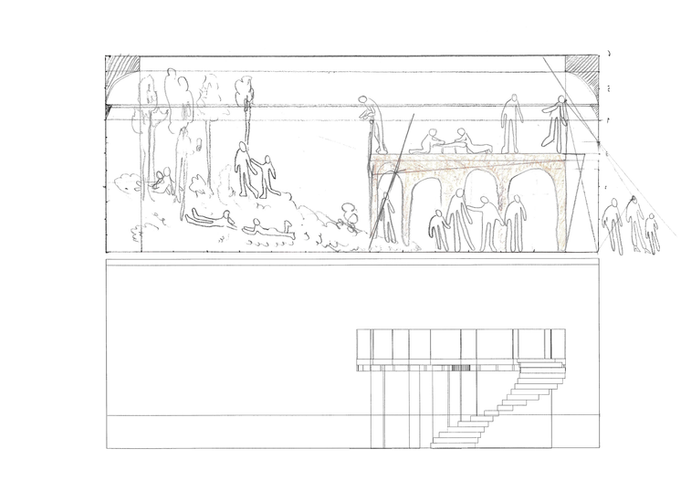

Sápmi Forever is a fictive transformation of a space in the former National Gallery in Oslo: a decolonial approach to a museum space with the means of interior architecture.

How can one tell the story of a past full of discrimination while creating a space that celebrates the future of Sámi culture? The research for this project also led to a field study where I drove 1500km through Northern Sápmi to talk to duojárat, artists, architects, curators, activists and children.

Nominated for the "Project of the Year" FKDS grant, 2022

Introduction

Prosjektbeskrivelse

Sápmi forever/ Nationalgalleriets fremtid

"The Norwegian National gallery has closed its doors temporally in January 2019 in connection with the artworks being moved to the New National Museum which will open in 2022. Plans in the future involve that the National Gallery is to be a part of the National Museum and eventually open again to publicly show art."

For the reopening of the gallery, I am suggesting to turn the prestigious Christian Langaard Sal into a space for discussion and education about Sámi art. The space is not designed to show art, but to enable a discussion about Sámi presence. Why not a gallery space? I belive that Sámi art is ought to be shown at the official and new National Gallery and not to be used to “fill” a gallery that just downgraded in status. What I claim to be more important is to create a space for meeting, a space that educates Non-Sámi about Sámi culture. In other words, I want the building and institution of the National Gallery to take responsibility for its past of discriminating against Sámi artists. I want to create a gallery that reflects on culture and belonging.

Sápmi Forever celebrates Sámi culture from an outside perspective. We all have much to learn from Indigenous peoples, and with this project I set out to educate myself about Sámi history, culture and traditions in a contemporary context.

The project takes a decolonial approach within interior architecture. I have done my best to dive deeply into research, yet I am aware that within the timeframe of this bachelor project I could only begin to grasp the tip of an iceberg. My work is grounded in dialogues with duojárat, artists, architects, art historians, researchers, activists and children. Through these conversations, I wanted to explore if and how a space can shift the narrative of Scandinavian history towards one that celebrates the Indigenous culture of Sápmi.

However, this project is not intended to be realised. If the transformation of a hall in the former National Gallery were to happen, it should not come from the hands of a non-Sámi designer. Sámi perspectives must be shaped by Sámi designers. I can learn from Sámi culture, but I can never create a Sámi piece of culture myself. In other words, this project taught me that as a designer one must also learn when not to design — sometimes the right act is simply to sit down and listen.

Still, to complete my Bachelor in Interior Architecture, I had to design a space. What you see here is my interpretation of a meeting place between Sámi and Norwegian art culture, based on what I have learned. For this project to be truly right and relevant, the Sáminess is yet to be added: Sámi artists, writers, duojárat, architects, designers and others willing to share their stories, experiences and knowledge. Only together with them can this space become what it is meant to be.

Phase 1

Research

The room I chose for my project is one of the most prestigious halls in the National Gallery. Christian Langaard is the reason an entire additional wing was built. His Dutch and Flemish art collection was one of the most important ones in Norway. In other words, a whole museum wing was built to host the precious gift of Dutch paintings. The interiors of the hall are inspred by Dutch and French Museums.

What makes art national enough to be shown at a National Gallery?

Underrepresentation of Sámi Art at the National Level

"After severing the personal union with Denmark in 1814, nation building dominated the artistic fields in Norway. Constructing a common national identity was important, and yet at the same time there was a tendency in the arts community to perceive Sámi artists as exotic and foreign 'Others'. Although there are some good exceptions, national institutions such as the Art Museum of Northern Norway and the National Museum rejected Sámi identity and history based on restrictive rules for what they could and wanted to exhibit."

IRENE SNARBY

Hill, Lalonde, C., Hopkins, C., & National Gallery of Canada. (2013). Sakahàn : international indigenous art. National Gallery of Canada., p.67.

"The Sámi disciplines dáidda and duedtie have not been made equal to – or completely accepted within – traditional Western or national art history (Danbolt; Persen 20). Sámi art has not been included in the national art sphere as equal to Norwegian art."

MAJA DUNFJELL

Gaski, Guttorm, G., Sámi allaskuvla, & Norwegian Crafts. (2022). Duodji reader : guoktenuppelot čállosa duoji birra sámi duojáriid ja dutkiid bokte maŋimuš 60 jagis = a selection of twelve essays on duodji by Sámi duojárat and writers from the past 60 years. Davvi girji. pp. 163.

Sápmi

Sápmi is the area where the Sámi people have traditionally lived in harmony with the surrounding natural resources. Sápmi’s borders are not formalised, but the area stretches over the Guoládat/ Kola peninsula in northwestern Russia, the Lapland region in Finland, the Norrland region in Sweden, the whole of Northern Norway and southwards to Engerdal, which is less than 300 km from Oslo, Norway’s capital.

The national states have disputed the historical extent of Sámi presence and settlements, but archaeological research has shown that Sámi people had a very early presence in some areas of Northern Scandinavia, dating back to when the last Ice Age in Northern Europe ended about 10,000 years ago. Although it is disputed to what extent found artefacts and rock art of that age can be identified with a specific culture or people, 2,000-year- old archaeological artefacts in areas of Finnmárku on the Norwegian side of Sápmi are seen as proto-Sámi.

There are also archaeological findings suggesting that two kinds of people, proto-Sámi hunter gatherers and proto-Norwegian farmers, lived on respective sides of the Trysil river as early as the Neolithic age, in an area corresponding to the southernmost Sámi settlement today.

The Sámi population is difficult to number, since there are no ethnic registration systems in Sápmi, except on the Russian side. Sources cite numbers ranging between 50,000 and 100,000, with at least half on the Norwegian side. Many Sámi people also live in the bigger cities outside of Sápmi. There are ten Sámi languages, belonging to the Finno-Ugric language tree. Kemi Sámi is extinct, and the rest are considered endangered languages by UNESCO, half of them critically so. Northern Sami is the language that is spoken by most Sámi- speakers today. Active assimilation policies have, however, led to the loss of Sámi languages, and thus there are many people who consider themselves Sámi without being fluent in a Sámi language.

Sami religion has animistic and shamanistic traits, with the noaidi as the advisor, healer and link between people and the gods. Centuries of Christianisation almost wiped out ancient religious practices, but even Christian Sámi people today have kept some of the knowledge, sayings and rituals connected to the ancient belief system, and the revitalisation of Sami spirituality is gaining strength. In Norway, Sweden and Finland, there are Sámi Parliaments called Sámediggis, but these have no sovereign power over lands, waters and other resources. The national states, to different degrees, consult the Sámediggis on matters that they consider of Sámi concern.

SUSANNE HÆTTA

Hætta, Finbog, L.-R., García-Antón, K., Moulton, K., & Office for Contemporary Art Norway. (2020). Mázejoavku: indigenous collectivity and art. Office for Contemporary Art Norway DAT., pp. 12-13.

Untitled, 2022

TOMAS COLBENGTSON

Prolog

Da de brente meg levende på noaidebålet

Hvem skulle tro

at det på grunn av alminnelige menneskerettigheter som nordmannen selv har

skulle oppstå et sånt helvete;

med én gang starter sjefifinga, samene får ikke gjøre sånn,

de får ikke gjøre slik,

samene er skitne, late jævler,

urenslige, tyvete sataner,

møkkete luseopphopninger,

drikkfeldig

tykjepakk.

Enn nordmannen?

Har samene noen gang

forbudt nordmannen å snakke sitt eget språk, forbannet nordmannen sin tro, forbudt dem å gå i kirken?

Har samene noensinne dratt til kirka deres, gått løs på folk der,

dratt dem ut derifra,

ordna et jævla stort bål

og brent nordmennene levende på det bålet

fordi de var i kirka?

Har samene noen gang svidd av alle norske kirker, brent og herjet,

med makt tatt nordmennenes hus

og forbudt dem å snakke norsk?

Har samene

slaktet, fratatt

og stjålet alt nordmennene eide,

og etterpå løyet og vridd på det,

sagt at det hører til dem?

Har samene

noen gang skrevet

sånne lover for nordmannen,

at alt tilhører dem,

for dermed å kunne sable ned nordmannen i retten siden de selv har skrevet lovene?

Ville samene

ha stressa seg opp

og begynt å forfølge norske barn, bygget store indoktrineringskamre for dem?

Ville samene

ha frarøvet dem deres barn, tvunget barna

til å bli hos dem selv for at det skulle bli

folk av dem?

Vi hadde aldri noen

agenda med dem,

å gjøre et annet menneske

så fredløst,

hvis de nå er mennesker, disse kaldblodige reptilene, så umenneskelige og følelsesløse

som de er

MARY AILONIEIDA SOMBÀN MARI

Sombán, Busse, T., Fredriksen, L. T., Kittelsen, E., Reibo, E., & Skåden, S. (2020). Beaivváš mánát : Leve blant reptiler. Mondo books, pp. 16-17.

Phase 2

Understanding / Field study

The Route

The trip began in Romssa/ Tromsø. Ice cold wind and snow hit our face when we left the airport on the way to pick up the rented car, a shorter-than- expected Ford Kuga with four wheel drive and studded tires. We had around 1200km ahead of us.

We spent the night in Gárasavvon/ Karesuando on the Finnish-Swedish border, sleeping in the rented car behind the local dental clinic. Gárasavvon is more of a polar highway hub and known for its trucker sauna. By dawn we continued our journey through the snowstorm up north to Guovdageaidnu/ Kautokeino. Guovdageaidnu/ Kautokeino is a rather small town but home to Juhl ́s Silver Gallery with an interior which is out of this world, the Sámi Allaskuvla (Sámi Univeristy of Applied Sciences) and Giant-Lávvu Rema1000.

In the evening we decided to continue the drive to Kárášjohka/ Karasjok. Kárášjohka is slightly bigger than Guovdageaidnu. It accomodates among other things the Sámi Parliament, Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš (Sámi Museum for Contemporay Art), RiddoDuottarMuseat (the Sámi Museum and Collections) and a swimming hall. We went to the swimming hall, a great place to not only talk to locals about the latest happenings in town but also to finally shower.

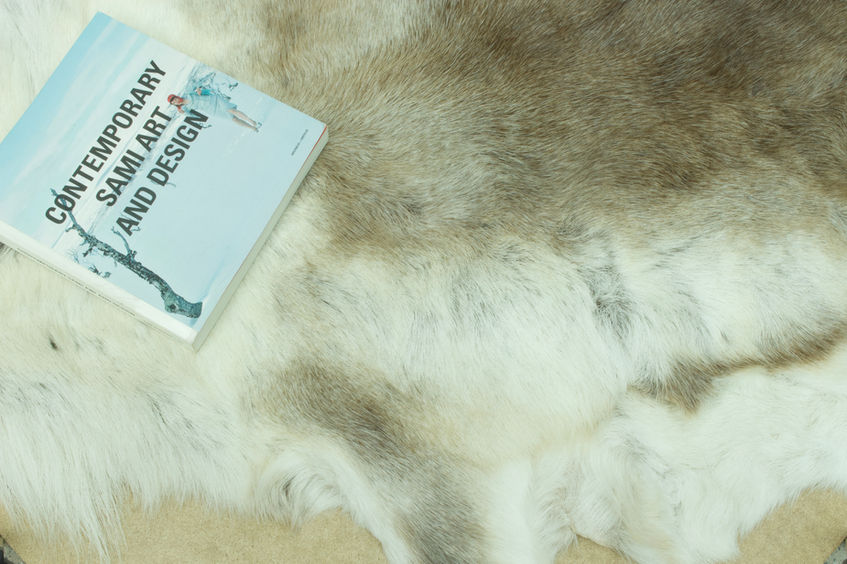

In Kárášjohka we slept in a wonderful forest, sat on reindeer pelts around the bonfire and saw the Northern lights dancing through the cold night. 27 degrees beneath zero. I tried to spot Sarvvis, the great reindeer in the sky, but I did not find it. Sarvvis is running from Fávdna, persistent hunter holding bow and arrow. However, Fávdna is not alone on the hunt: A couple on skis and their dogs are also crossing the night sky. Among others, Boahji, the Pole star, is as well aiming his bow towards Sarvvis. If he shoots all stars will fall from the sky and it will be the end of the world. After hours of suspense, the sun rises and the hunt is over for the night.

Artist Interview with

Joar Nango

I met Joar Nango in his Studio at TKF Loftet. The Tromsø Kunstforening (TKF) is since 1924 located in the former Tromsø Museum. Today it not only hosts 450 square metres of gallery spaces and a loft with ateliers, in fact, it has in recent years also become the home and nesting place for the black-legged kittiwakes (Krykkje, a seabird in the seagull family). After they lost their habitat at sea by Spitsbergen and Svalbard they came closer and closer to big cities by the coast and found a new home. Joar lovingly calls the TKF building the bird mountain. The sound of uncountable krykkje is omnipresent at his studio which seams to be the heart of the bird mountain.

However, Tromsø Kommune put up nets in front of the windows and niches on the building to prevent the seagulls to nest. The krykkje colony is therefore in a heartbreaking agitation. They flew thousands of kilometres over the Barents Sea to discover that their new habitat has also been taken from them. To stay or to leave, the decision will affect a whole generation of this krykkje colony.

Joar welcomed us with a warm cup of coffee wearing his rainbow platform crocs. Later I realised that platform crocs are the ultimate garment in order to quickly cross a parking lot without getting your wool socks wet from the snow. He sat down in his armchair which is covered in all kinds of pelts: seal, a tiny black goat and two grey lambs. Joar is a collector. He collects all kinds of fantastic things, crafted by nature or by the hand of a variety of artists and friends from all over the world.

We spoke about Girjegumpi and European Everything, his architecture/ art work for Documenta 14 in Athens 2017. We spoke about the Giant Lávvu syndrome and laughed at why every public Sámi building in the 80s just looks

like a giant Lávvu. We spoke about Sámi colours and he told us that there is strength in the meaning of strong colours and that it would not

be the same with weaker, more pastel, colours. We talked about Sámi presence within art institutions in Norway. Where should the (since the 1970s planned but always laid off) Sámi Museum of Art be? Within the unofficial borders of Sápmi or in the Norwegian capital next to the Norwegian National Gallery? If in Sápmi then in easy accessible Romssa/ Tromsø or in deeply Sámi Kárášjohka/ Karasjok?

Questions that nobody has a definite answer for. However, we came to the conclusion that Sámi presence should be everywhere. One should not be forced to travel over 3000km north from where the majority of inhabitants of a country live just in order to educate oneself on the Indigenous people of North Europe. Knowledge should be accessible overall.

At the end of the visit Joar gave me a gift. A postcard collection from Indigenuity project in collaboration with Sámi artist Silje Figenschou Thoresen. The postcards show ways of designing things and solutions that can be described as both indigenous and ingenious.

Joar Nango in his studio

Sámi architecture identity

Our image of the built environment of the Sami territories in the far north is dominated by two preconceptions: on the one hand the image of particular structures like turf huts and the lavvo, the Sami tent, and the reinterpretation of these structures in new public buildings like the Sami parliament building in Karasjok, and on the other hand the spread of anonymous suburban housing that at first glance have no Sami characteristics. Both these conceptions are true, spanning from a low-key attitude to everyday life to the symbolism of monumental architecture, but both are incomplete.

Modern Sami settlements are in fact challenging the way the urban middle class organise and use their domestic environment. A Sámi dwelling contains the familiar domestic functions, but in addition it is the setting for a number of other activities, related to both working and an extended social life; the outdoor areas in particular give room for an active and creative way of life. And it is these activities, rather than the static elements of buildings and furniture, that give the places their identity; the structures that bind the Sami settlements together are social, not physical.

SUNNIVA SKÅLNES

Sunniva Skålnes is an architect with PhD background from NTNU, researcher and senior advisor to the Sámi Parliament.

Lavvo og gamme som mønster

Eit lite repertoar av former vart tidleg teke i bruk då samiske fellesskapsbygg skulle formast. Av desse vart lavvoen og gammen dei mest brukte. I tillegg vart bruk av naturmateriale og primærfargar sett på som samisk, både lokalt og frå storsamfunnet. Mest utan unntak var det norske arkitektar som forma den nye arkitekturen.

[...] Lavvoforma er blitt eit signal som på tydeleg vis fortel vegfarande kor dei er.

[...] Det sterke symbolinnhaldet i lavvoforma har også ført til overbruk, og til at dette formelementet til dels er blitt brukt på ein for lite gjennomarbeidd måte. Kultursenteret Árran på Drag er eit eksempel på eit bygg der lavvoforma er kopiert og forstørra og er tydeleg til stades i den ytre forma, men vanskeleg å finna igjen i interiøret. Både dei funksjonelle krava eit større kontorbygg stiller, og lokaliseringa i eit sjøsamisk område gjer det naturleg å forventa bruk av andre formelement som symbol for den samiske tilknytinga. Bruk av lavvoforma i utstrekt grad har også ført til at forma har blitt tømd for eit funksjonelt innhald og blitt ståande igjen som rein dekorasjon, slik me ser til dømes i nyare turistanlegg som kafeen i Máze.

SUNNIVA SKÅLNES

https://www.arkitektur-n.no/artikler/samtidig-samisk-arkitektur

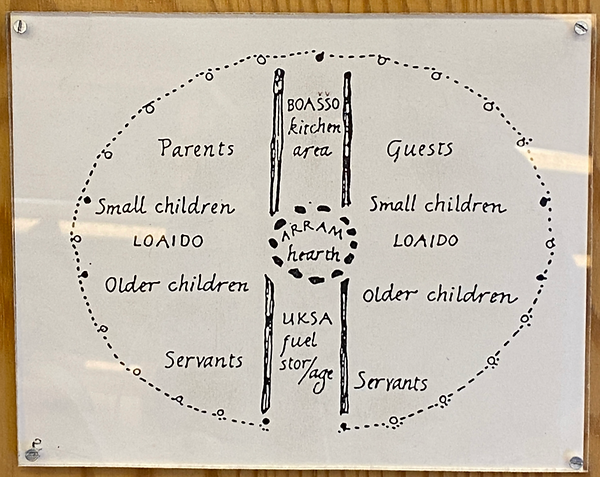

Real lávut

A lávvu (pl. lávut) is a Sámi tent-like construction, traditionally used as a temporary residence for Sámi who are moving from region to region, but also functions when needed for a more permanent residence. It has been carefully developed over generations and perfectly adapted to a nomadic way of life and the harsh northern climate. The lávvu is an excellent example of how an air-conditioned living zone with minimal consumption of energy and materials can be created . In other words, if its minus 20 degrees celcius, you can sit in a t-shirt around the fire without freezing.

A lávvu is not to be blown up in size and to be used as a stiff and empty construction housing something which has nothing to to with what one would use a lávvu for.

The interior of a lávvu is organized into different zones for different functions. Even though they are spacially very closed to each other, the separation of them is very strict.

Indigenous Aesthetics

“Western” academic terminology often proves ill-suited to describe the worldview and attitudes of an Indigenous culture; likewise, the norms of behaviour and value systems of an Indigenous culture can seem strange for someone operating within a Western sense of the world and self.

[...] Aesthetics in a much wider context than the common dictionary definition of what is regarded as “beautiful” - a problematic concept since the notion of “beauty” is relative and contextual. We can find a number of examples of the fact that Sámi had no desire to categorise human activities or one’s environment in any rigid either/ or dichotomy but rather on the basis of an array of choices of varying utility. Value judgments are not based on outward appearance so much as the relation of a thing’s form to its intended purpose.

Concerning objects made by people, for instance, Sjulsson notes that “ugly” objects are those which are scruffy, uneven, with corners or edges that stand out.

Most objects are neither beautiful nor ugly.

“Beautiful” things, Sjulsson characterises as “symmetrical and streamlined, with no protruding corners or edges, well adapted for their intended purpose.”

In Sámi tradition, making something beautiful entailed making it functional,

ensuring that it was grounded in a solid foundation of knowledge, competence and technique.

Do traditional values have any utility in a postcolonial world? This question is of great relevance to researchers in Indigenous studies. Another Sámi example, here, could have been the terminology, or rather epistemology, pertaining to different ways of performing juoigan, a genre of traditional Sámi singing. However, that would necessitate recognising a whole range of specific Sámi terms describing the variety of aesthetics in connection with juoigan. While this would have been an interesting endeavour, it would bring us into another field of artistic expressions inhabiting its own rules and regulations.

HARALD GASKI

Indigenous Aesthetics: Add Context to Context

Gaski, Guttorm, G., Sámi allaskuvla, & Norwegian Crafts. (2022). Duodji reader : guoktenuppelot čállosa duoji birra sámi duojáriid ja dutkiid bokte maŋimuš 60 jagis = a selection of twelve essays on duodji by Sámi duojárat and writers from the past 60 years. Davvi girji. pp. 218-229.

A Way to Calm Reindeer

I have learned to explain juoigan in a way that can be understood by people from other cultures. In so doing, I must first say something about the Sámi view of the nature of Western culture. The Western view emphasises growth, reductionism, and speed. To the Sámi, this perspective seems rigid, hierarchical, and compartmentalised. It reflects a spirit that values mathematics, marching music, angularity, compartments, and formulas. Indigenous people, have a different way of thinking.

Human beings are a part of nature and not its master. All the parts of nature are interdependent and influence how things happen... as they should happen. Nature exists in a state of harmony that embraces all its labyrinths. Sharp edges crumble in the natural environment. The air, the egg, and the wave are nature’s shapes. There is fluidity between all parts.

The one who catches every single fish in the lake in order to eat will also die in the end. Inner space with its invisible dimension is of much greater interest than mathematical calculations. Origin, unity, merging is paramount. Even a luohti billows, merges, moves on.

Another aspect that unites Indigenous people is their philosophy of life. Humans are part of nature. To make things by hand is part of life. The concept of culture does not necessarily have to include division and compartmentalisation. There is no separate “art” or “music”. Juoigan is not just music. The function of juoigan is much wider than that. Juoigan is a way to make social connections. A way to calm reindeer. To frighten wolves. The intent of juoigan had never been to present it as an art form-which assumes an audience. Juoigan was used to recall memories of friends, even enemies, places and regions, animals.

Juoigan was also a means to move into a spiritual world, and that makes it religious. The luohti does not have a specific length nor a specific beginning or end. One can use words-or not-in the luohti.

NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ / ÁILLOHAŠ

A Way to Calm Reindeer

Gaski, Guttorm, G., Sámi allaskuvla, & Norwegian Crafts. (2022). Duodji reader: guoktenuppelot čállosa duoji birra sámi duojáriid ja dutkiid bokte maŋimuš 60 jagis = a selection of twelve essays on duodji by Sámi duojárat and writers from the past 60 years. Davvi girji. pp. 154-156.

Case Study, Kautokeino

Juhls Silver Gallery

The Juhls Silver Gallery is an atelier, a home, a café, a workshop, a museum, an art gallery and a design shop in one building. The building is a adventure through Sápmi’s cultural landscape and Frank and Regine Juhls are telling it through architecture and interior ornamentation. It is a place that shows so much love and dedication and detail in every corner that it is impossible to take it all in in one visit. The house is designed by Regine and Frank themselves and grew over the years into the wonderland of shapes it is today. The forms are inspired by the arctic nature, how wind and snow and the flora around behave.

Case Study, Karasjok

SDG Gallery

Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš (SDG) was established in Kárášjohka in 1986 and is today the leading international center for contemporary Sámi art. Its mission is to connect Sámi artists and audiences, presenting Sámi contemporary art within a global context while remaining deeply rooted in Sápmi. SDG aims to foster understanding, dialogue and artistic freedom—serving both as an exhibition space and a cultural bridge between the Sámi community and the wider world.

Visiting SDG felt like stepping into a new world, yet one that somehow felt familiar. The gallery is housed in a former school building—an old white wooden house whose exterior contrasts sharply with the minimalist white box interior. With its polished concrete floors and smooth white walls, it could easily be mistaken for a gallery in Oslo or Berlin.

When I spoke with director Kristoffer Dolmen, he told me about the building’s painful past: it once served as a school that worked actively to assimilate Sámi children, forbidding them to speak their language. Some of today’s visitors once attended that school and still find it difficult to enter. Beneath the smooth concrete floors lie memories of silence and erasure.

Now those same walls display powerful expressions of Sámi identity. SDG is home to some of the most compelling exhibitions of Sámi art anywhere, works filled with strength, emotion and renewal. The transformation of this building feels symbolic: what was once a place of cultural suppression has become a space for cultural pride and creativity.

Including SDG in this case study of Sámi buildings raises an interesting question – can a white box gallery be considered Sámi architecture? Perhaps not in form but certainly in spirit. Its Sáminess lies not in the shape of its walls but in its purpose: to give Sámi art visibility and recognition in a global art world and to reclaim a space once meant to erase Sámi culture as one that now celebrates it.

Case Study, Tromsø

Árdna Pavilion

Árdná serves as a gathering place for smaller seminars, exhibitions, representation and duodji. The building is constructed with an open round-timber structure and a longitudinal skylight facing west. At its center lies a sunken fireplace. Both construction and material use follow Sámi building traditions and rely on local resources. The round pine logs and paneled walls inside and out are made of untreated pine from Målselv, felled at new moon in line with Sámi custom. Doors and windows are made of pine and glass and the floor is an oiled solid pine parquet with oak details. A hollow pine trunk along the front façade functions as a roof drain.

Inside, the back wall is clad with natural stone veined with copper: Barents Red from Grasbakken in Nesseby and Barents Blue from Bugøynes in Sør-Varanger. The stone is polished indoors and finely ground on the exterior. Wooden pillars rest on rounded stone cylinders of Barents Blue. The hearth area and floor are made of quartzite slate from Nordreisa while the fireplace itself contains gravel and river stones from Manndalen in Kåfjord, chosen by local duojárat.

Above the fireplace, fiber-optic lighting on an acrylic panel depicts the starry sky as it appears at midnight in January with Sarvva at its center. Tables, shelves, stools and screens were designed specifically for the building by the architect while the leatherwork, textiles and wooden details were created by Sámi craftspeople who use the space. Árdná exemplifies what can be achieved when architectural design and local craftsmanship meet with mutual respect. It is a space shaped by collaboration.

Phase 3

Translating / Design

Sámi Functionalism

Understanding of landscape and climate

Ability to improvise

Resource economic design

Combining local materials in practical and spontaneous ways

Knowledge lies in the craft

Architecture serves to bring people together

Antropometry as a size guide

Temporariness, natural decaying as the goal

A celebration of tradition and innovation

Architecture that connects the visitor to the surroundings

How I adapted the values of Sámi functionalism into my practice

In order to understand the room better, I approached it artistically. For the outside observer, these might seem rather abstract, but for me they are diagrams of intimacy, tension, movement and warmth in a room.

They helped me find the position of a core in the room and estimate where there are places where visitors walk, stand and watch and would settle for a conversation.

They also show the dynamic between entrance and the rest of the space. On the bottom left picture, one pixel equals one square metre. Cold colours visualize spaces of movement and warmer coloured squares show intimacy and rest. Through printing out plan drawings on wool I was able to give a type of fluidity and tactility to something that tends so be very mathematical and rigid.

Anthropometric Appraoch

The feeling of being small while standing beneath the 6 metre high ceilings did not benefit the experience I wanted to give people. I wanted to take away the symbolical predominace of the Norwegian state, manifested in prestigious out-of-human- scale proportions. Somehow the room had to become more human-scaled, the ceiling had to come down, or the people had to come up to the ceiling. The latter is something I admire about Sámi architecture: All spaces are within reach. You have control over the space because your hands reach to the ceiling. You can fix it on your own. You are independent.

By creating a pavilion with accessible roof top, I wanted to achieve exactly this. Suddenly the Langaard hall would not seem so tall and and dominating. Suddenly you are not looking up anymore to the cornice where it said Christian Langaard Gave in golden letters. Instead, you stand on eye hight with it. It is a matter of perspective.

I was looking for a shape that was both geometric, maximalist and in tune with Sámi ornamentation. Throughout Sápmi one can find especially many triangular ornaments which create a bigger pattern. I therefore decided to implement the tips of triangles in my design.

The round shape stands for unity and togetherness, values that I wanted this pavilion to represent. It also creates a feeling of collection and belonging

Phase 4

Installation

The work consists of a model in mixed media, digital prints on wool and silk, a sculpture in acrylic plaster, an installation with mixed media and sound, video documentation of the field study, analogue and digital photography, a text publication